For years, however, the government of China has refused even to speak to His Holiness. Beijing appears to realize that it needs Tibetan Buddhism on its side to make its rule of Tibet legitimate to the Tibetans. But for inexplicable reasons, Beijing cannot bring itself to work with the current Dalai Lama, who has publicly offered many concessions to Beijing.

Beijing has a plan, however, already in place. It has assumed authority to manage the rebirths of all Tibetan lama lineages, and it has declared it will name the 15th Dalai Lama after the 14th has gone.

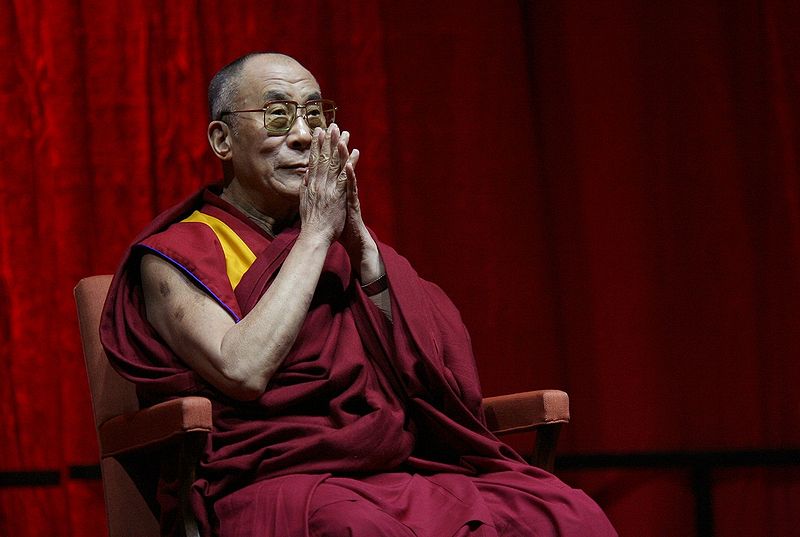

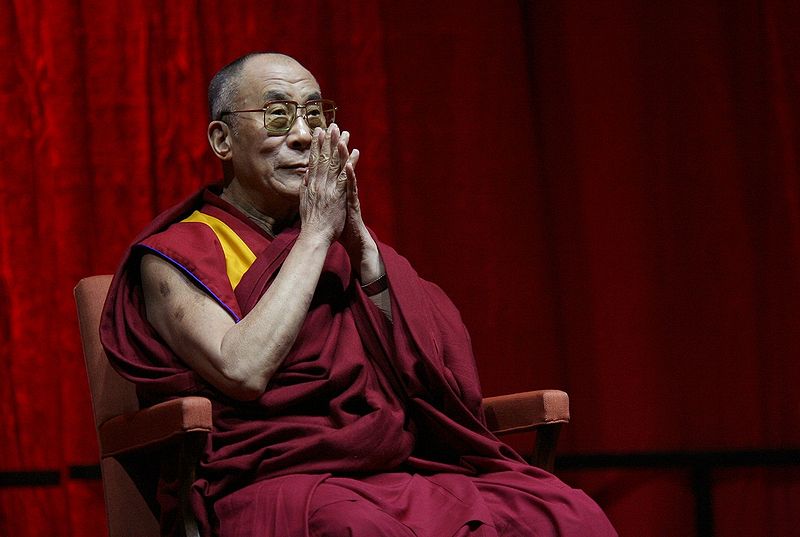

Photo by Yancho Sabev, via Wikipedia Commons

Government-Managed Reincarnation?

In 2007 China’s State Administration of Religious Affairs released Order No. 5, which covers “the management measures for the reincarnation of living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism.” In short, rebirths require a government permit. As ridiculous as this may sound to us, Beijing is deadly serious about this. Its aim is to be sure all religious authority within Tibetan Buddhism is under its control.

The current Dalai Lama appears to be in robust health. But what will happen when he’s gone, both to Tibetan Buddhism and Tibet?

This much is certain, barring a radical change of leadership in Beijing: Within days, if not hours, of the passing of the 14th Dalai Lama, the government of China will announce that it has begun the process of identifying the 15th Dalai Lama. And I doubt much time will pass before Beijing reveals the identity of the tulku and begins to prepare for his enthronement as Dalai Lama.

You might ask, since when does the government of China choose Dalai Lamas? Well, since never, in fact. But Beijing claims it has that power now, based on three arguments.

Patrons and Priests

First, China’s claim of sovereignty over Tibet rests largely on the historical relationship between the Manchu emperors of China and the Dalai Lamas.

The Manchu emperors of the Qing Dynasty ruled China from 1644 to 1912. Beginning with the 5th Dalai Lama (1617-1682), a patron-priest relationship developed between the succession of Dalai Lamas and the succession of Qing emperors. This meant that the emperor personally was a lay patron of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lamas, in turn, provided religious instruction, beneficial rituals and other spiritual services to the emperor. The Dalai Lama was considered the emperor’s guru, not his subject.

After that, the relationship between Tibet and China was complex. China sometimes sent military aid to Tibet; this was in China’s own interest, since Tibet was at its western border. China did not attempt to govern Tibet; nor did China ask for taxes or tribute from Tibet. However, the emperor did appoint “observers,” called ambans, who acted as the emperor’s eyes and ears in the Tibetan capital. And the ambans often did insert themselves into Tibetan affairs, both political and religious. Historians say they did not identify reborn lamas, however.

After the Qing Dynasty ended in 1912, and China was (more or less) a republic, the 13th Dalai Lama issued a “Tibetan declaration of independence” saying that the patron-priest relationship had been with the individual Manchu emperors, not the government of China, and with the abdication of the last Qing emperor that relationship had faded “like a rainbow in the sky.”

However, from the time of Mao Zedong China has declared that not only were the Dalai Lamas the subjects of the emperors, the old patron-priest relationship carried over from the empire to the republic — whether the Dalai Lama agreed or not, apparently.

For more about the history behind China’s claims to Tibet, see “The 7th Dalai Lama, Kelzang Gyatso: A Life in Turbulent Times” and “Tibet and China: History of a Complex Relationship.”

The Golden Urn

Late in the 18th century a messy spat involving high lamas of the Kagyu school and an invading army of Gurkhas caused the Qianlong Emperor to demand reforms in the process of choosing high lamas. A disproportionate number of high lamas were from the same aristocratic family; favoritism in the selection process was an open secret.

One of the reforms agreed upon was that the future rebirths of lamas would be chosen by means of drawing lots from a golden urn, to be kept at Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. The historical record reveals the Tibetans really didn’t use the urn that much, however. When they did use it they were able to rig the result, probably by making sure the lots all bore the name of the candidate already chosen. This token ceremony appears to have been carried out for the 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas. By the time the 13th Dalai Lama was chosen, however, even a token ceremonial use of the urn had been abandoned.

Read More: The 8th Dalai Lama and the Golden Urn

Today the government of China possesses the golden urn — a couple of them, in fact — and insists that the rebirths of lamas may be recognized only by the golden urn lot-drawing method, because that is “traditional,” in spite of its not being traditional at all.

The Panchen Lama

The Panchen Lama is the second-highest lama of Tibetan Buddhism, and one of the traditional duties of the Panchen Lama is to identify the rebirths of Dalai Lama. Likewise, one of the traditional duties of a Dalai Lama is to identify the rebirths of Panchen Lamas.

Read More: The Panchen Lama — A Lineage Hijacked by Politics

The current acting 11th Panchen Lama, Gyaltsen Norbu, was chosen by the government of China, however. Raised and trained by private tutors in Beijing, Norbu’s primary function is to issue statements praising the government of China for its wise leadership of Tibet.

The Dalai Lama’s choice — a six-year-old boy named Gedhun Choekyi Nyima — and his family were taken into Chinese custody in 1995, just two days after his identification as the 11th Panchen Lama became public. They have not been seen since.

As far as Beijing is concerned, the ducks are in a row — they have the golden urn and the Panchen Lama, and they have concocted a revisionist version of history that makes the Dalai Lamas vassals of China. In their minds, that gives them all the authority they need to choose the 15th Dalai Lama.

What the 14th Dalai Lama, and Tibet, Might Do

On July 6, 2015, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama observed his 80th birthday. He has lived longer than any other Dalai Lama except, possibly, the first, who is believed to have lived to age 83 or so. But he’s not going to last forever.

His Holiness has said, at various times, that he might choose a successor before he dies; he might come back as a woman; he might not come back at all.

Even if high Gelugpa lamas outside of Tibet identify a new Dalai Lama through traditional esoteric and mystic methods, in these fragile times Tibetan Buddhism can’t place itself on hold for 20 years until he grows up. It is expected that many of the Dalai Lama’s duties as the public face of Tibetan Buddhism will pass to His Holiness the 17th Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje. The 17th Karmapa, the highest lama of the Kagyu school, is a young man already popular with Tibetans.

As for Tibetans, they have clearly never accepted the faux Panchen Lama, and it seems unlikely they would accept a faux Dalai Lama. China seems to be going to a lot of trouble for nothing. And with no living Dalai Lama to discourage violence, things may get worse for China and Tibet once His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama is gone.

[This is an article I wrote for the Buddhism section of About.com. However, since About.com has removed it from their servers, all rights revert to me.]