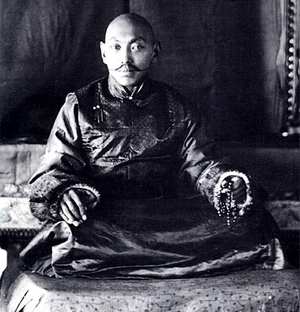

In 1913, His Holiness the 13th Dalai Lama issued what many call a “declaration of independence” for Tibet from the Republic of China. The 13th Dalai Lama’s position was that the Gelugpa leadership of Tibet had a relationship with (but were not subjects of) the the Manchu Emperors of China, not the nation-state of China. When the Qing Dynasty was overthrown in 1911, any ties between China and Tibet were severed, His Holiness said.

The proclamation, given to the people of Tibet, begins by affirming the Dalai Lama’s authority to rule Tibet. He evoked Tibet’s ancient kings and Avalokiteshvara, patron deity of Tibet, from whom the Dalai Lamas emanate. This part of the proclamation follows a tradition begun by the 5th Dalai Lama.

His Holiness then described the relationship with the Manchu emperors as a “patron-priest” relationship, which was something significant in the histories of both Tibet and China, going back to the time of Genghis Khan. High lamas of Tibet acted as spiritual advisers to Mongol and Chinese rulers, and in return received protection from their powerful disciples. For example, his patron/disciple Gushi Khan secured the leadership of Tibet for the 5th Dalai Lama.

A Sakya lama named Pagpa gave empowerments and teachings to Kublai Khan (1215-1294), which made the two patron and priest. Since Kublai Khan ruled China, and the Sakyas were the tenuous rulers of Tibet at the time, this patron-priest relationship is sometimes evoked by China today as part of its claim to Tibet. But historians tell us the Great Khan would not have seen Pagpa as his subject, but as his guru.

The 13th Dalai Lama’s proclamation begins:

“I, the Dalai Lama, most omniscient possessor of the Buddhist faith, whose title was conferred by the Lord Buddha’s command from the glorious land of India, speak to you as follows:

“I am speaking to all classes of Tibetan people. Lord Buddha, from the glorious country of India, prophesied that the reincarnations of Avalokitesvara, through successive rulers from the early religious kings to the present day, would look after the welfare of Tibet.

“During the time of Genghis Khan and Altan Khan of the Mongols, the Ming dynasty of the Chinese, and the Ch’ing Dynasty of the Manchus, Tibet and China cooperated on the basis of benefactor and priest relationship. A few years ago, the Chinese authorities in Szechuan and Yunnan endeavored to colonize our territory. They brought large numbers of troops into central Tibet on the pretext of policing the trade markets. I, therefore, left Lhasa with my ministers for the Indo-Tibetan border, hoping to clarify to the Manchu emperor by wire that the existing relationship between Tibet and China had been that of patron and priest and had not been based on the subordination of one to the other. There was no other choice for me but to cross the border, because Chinese troops were following with the intention of taking me alive or dead.

“On my arrival in India, I dispatched several telegrams to the Emperor; but his reply to my demands was delayed by corrupt officials at Peking. Meanwhile, the Manchu empire collapsed. The Tibetans were encouraged to expel the Chinese from central Tibet. I, too, returned safely to my rightful and sacred country, and I am now in the course of driving out the remnants of Chinese troops from DoKham in Eastern Tibet. Now, the Chinese intention of colonizing Tibet under the patron-priest relationship has faded like a rainbow in the sky.”

The remainder of the proclamation, which you may read on this page, lists the 13th Dalai Lama’s intentions for the future direction of Tibet.

Also in 1913, the provisional president of the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai, wrote the Dalai Lama asking for his allegiance to his “mother country.” The letter promised to overlook the Dalai Lama’s “former errors” and bestow on him a long title that began with “Loyal and Submissive Vice Regent.” His Holiness replied that he hadn’t asked for any titles, and that he “intended to exercise both temporal and ecclesiastic rule in Tibet.”