This is the prepared text of a talk I gave on Zoom at Treeleaf Zendo, June 21, 2020. There is a video recording here.

I want to speak today about why I think it’s important for Zen students to know something about Zen history.

My first Zen teacher, the late John Daido Loori, used to say that we all live in a box, and the dimensions of the box are made up of who we think we are and what we think our life should be.

The function of psychotherapy and most popular self-improvement programs is to remodel the box ― bring in nicer furniture, maybe expand the space, put in some windows to let light in. But the function of Zen is to help us realize that there is no box.

And it’s only by looking closely at what the box is made of that the ephemeral nature of the box is revealed.

Stories are a common element of boxes. As we live our lives we tend to craft a personal narrative that is all about “me” ― who I think I am, what I think my life should be. The dramatic tension of our story is created by all the ways circumstances frustrate us by not conforming to our expectations and giving us what we want. And deep down, perhaps we cling to a hope that eventually the plotlines will bend in our favor and we can live happily ever after.

Maintaining this personal, ongoing story in which we are the star is one of the ways we maintain our belief in a continuing, permanent self. It’s how we craft our personal identity. The Buddha understood this, and he taught people how to break the connection to their narratives through mindfulness. By paying moment-to-moment attention just to what is, without judgments or intellectual filters or placing experience in any other context, we can begin to realize the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves aren’t reality, and that person starring in our story isn’t really who we are.

A few years ago the Zen teacher Norman Fischer published a book called Sailing Home that is about exploring our personal stories. He wrote that when we stop getting lost in our own plotlines, with their tensions and expectations, we begin to see the feedback loops and old tapes that keep us stuck in suffering.

In the book, Norman Fischer suggested an exercise in which we begin with our earliest memory and then tell our life story as a story and not as a resume. Take two or three memories from childhood, from adolescence, from early adulthood, and so on, and then create a story that connects the memories. Then, go back, dredge up a different set of memories, and do it again. You might find you’ve told two very different stories about two apparently very different people. This exercise might put the question of “who do you think you are?” in a new light.

However, I think it also has to be said that none of us can ever stop crafting a personal story. It’s something we humans are wired to do. We just need to make sure our story is honest and that if provides a healthy psychological foundation for practice and for being a functional human being. And perhaps we shouldn’t take the story too seriously.

Now, history might be defined as the creation of an ongoing narrative on a collective scale. I suspect historians would hate that definition, but let’s go with it for now. In ancient times, what was called history was mostly folktales and myths, some of which might have been based on events that really happened, although not necessarily. These narratives were critical to creating the identities of tribes, or clans, or ethnic groups, or kingdoms. They told people who they were in a collective sense, as members of a particular group. Sometimes histories had to be revised when there was a change in the group, such as a new dynasty conquering an old one. Often when that happened stories about the old kings were forgotten and their images were smashed and replaced.

In the modern era, scholars took hold of history and insisted it be only about events that really happened. That’s a wonderful ideal that hasn’t yet been fulfilled. It is a fact that even now history is revised all the time as new generations of scholars bring new sensibilities and points of view to it.

If we go back to the exercise about creating different stories about ourselves based on different sets of memories, you can apply that to how historians have, consciously or unconsciously, shaped our views about things that have happened in the past. You can take this set of facts and interpret them this way to tell this story; you can take that set of facts and interpret them that way to tell that story. And the two stories may both be factual but still contradict each other.

Right now in the United States we’re having a struggle over relatively recent history. The American Civil War ended 155 years ago, not in 437 BC, and there are vast archives of records documenting exactly what happened. Yet we can’t agree on how that history is told.

In spite of all the memes on social media that complain about people living in the past, the truth is that even though the war is long over, the history of it is very much part of the collective meta-box Americans live in. Much of the standard history of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era that followed, and the way that history was taught in American schools for more than a century, was crafted by southern scholars who were Confederate apologists. And these apologists did a bang-up job of indoctrinating generations of American students into a whitewashed and highly romanticized perspective of that part of our history. In other words, thanks to the way this part of our story is told, we have avoided confronting and atoning for slavery all these years.

The facts of this history cannot be disputed. The people who pushed the South into secession were very open in their letters, speeches, and official documents that their primary objective was to maintain a white supremacist culture and the institution of slavery. That’s what they were all about. There is copious documentation for this. Yet that plain fact was not being taught in schools when I was a student, and I don’t know how much it’s being taught now.

So in much of American popular culture, which is the place where we tell our stories about who we think we are and what we think America should be, the Confederacy was about dashing and noble gentlemen warriors fighting for some fuzzy idea of states’ rights or even liberty, not about wealthy slave owners desperate to maintain their wealth and status as lords of a system that was worse than feudalism.

Newer generations of academic historians to this day are working to counter the pro-Confederate romanticism still embedded in American history textbooks and popular literature to tell a more honest story of the Civil War that doesn’t try to pretend it wasn’t about slavery. But I think that must be done before the nation can finally move on and live up to its own ideals of justice and equality. Until we can tell our story of our past correctly, we’re not going to get the present and future right, either.

Buddhist history also has been subject to considerable myth-making and revision. There is very little of the first five or so centuries of Buddhist history that we know with any certainty. What records that we have are fragmentary and conflicting, because they were compiled after the fact by people with obvious points to prove and axes to grind. These records may contain some clues but can’t be accepted at face value as historical fact.

In recent years early Buddhist history has become something of a blank slate on which people, in the West especially, have painted their own versions of what they want it to be. And apparently what they want it to be is more European.

Currently some western philosophy professors and some authors of popular Buddhist books have worked very hard to pull the historical Buddha out of India and move him closer to Europe, especially Greece.

Now, there really is reason to believe there was cross-pollination between Greek and Buddhist civilizations for a time. As I wrote in the first chapter of The Circle of the Way, beginning about the 2nd century BCE and through the early centuries of the first millennium CE, a large part of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and beyond, was a center of Buddhist civilization, primarily Mahayana Buddhism. And this same area was a crossroads of civilizations in which Greek, Roman, Persian, Indian, and possibly Chinese cultures intermingled. This is important to Zen because we know that most of the Buddhist monks who introduced Buddhism to China in the early first millennium CE came from this same area, following merchants east on the Silk Road into China. So if people see some influence of Greek thought in Mahayana Buddhism, it’s a good guess that’s where it happened.

But “some influence” isn’t good enough for some people. In recent years I’ve seen people who speak with authoritative voices declare that the historical Buddha probably wasn’t influenced by the religions and philosophies of India very much, if at all. Let me just say without going into a lot of detail that that position is utterly unsupportable.

And I ran into a scholar recently who was very sure that the Mahayana doctrine of emptiness appeared suddenly in Buddhism from Greek texts smuggled into monasteries and did not evolve naturally and organically from the historical Buddha’s teachings, as it certainly seems to have evolved. Apparently Asians needed Greeks to explain it to them.

I’m only going to say that one should be enormously skeptical of attempts to make the Buddha and Buddhism more European and less Asian, even when the person making these claims teaches in a university and has a ton of Ph.D.s I am not saying that these people are consciously racist, but I honestly do believe their, shall we say, ethnocentric biases are causing them to project things they want to see on Buddhist history that aren’t actually there. Historians are human beings, and unfortunately the discipline of history has no equivalent to the scientific method to filter out biases.

Now we have Buddhism introduced to China, beginning in the 1st century CE. And now I’m going to be challenged to pronounce Chinese names; let me warn you that I spell better than I pronounce. But I’ll do my best.

China was the great petri dish for Mahayana Buddhism that cultured much extraordinary scholarship and a rich diversity of schools, including Huayan, Pure Land, and Tiantai as well as Zen, which of course in China was called Chan.

In the first few centuries of Buddhism in China there seem not to have been rigid differences among schools. All Buddhist monastics received the same ordination; one was not a Tiantai nun or a Huayan nun, but a Buddhist nun. Monastics often traveled from one teacher to another seeking the dharma, and often they didn’t limit themselves to teachers of just one tradition. That said, in time sectarian rivalries formed, and self-preservation demanded that a tradition not only have highly regarded teachers but a respectable backstory.

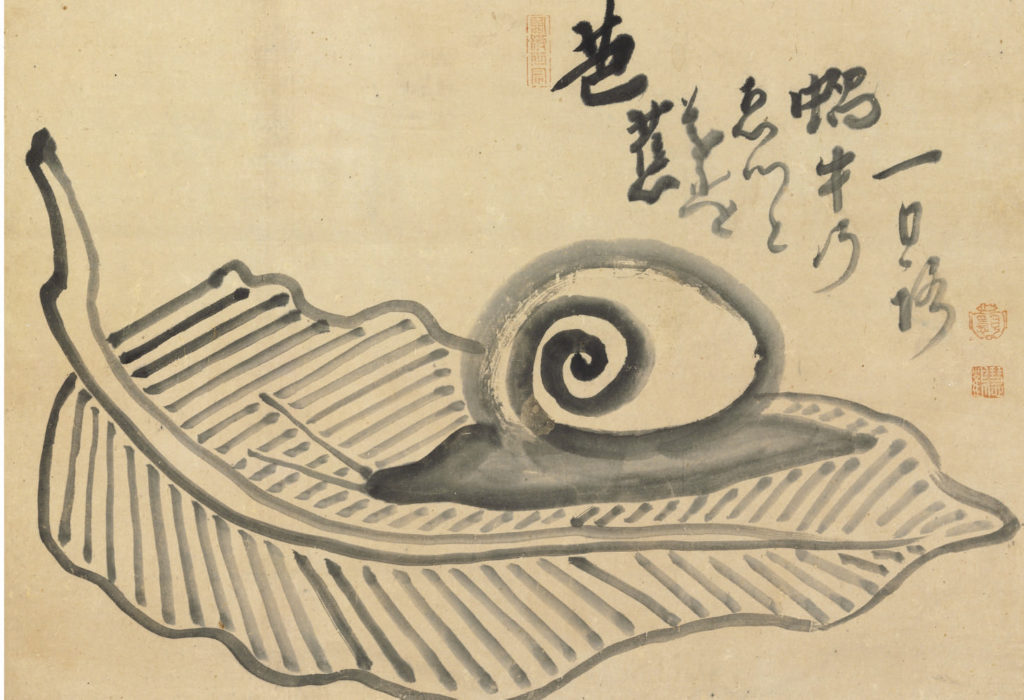

Most of the stories we’ve all heard about the Six Patriarchs and early Chinese masters come from records compiled during the Song Dynasty, which lasted from 960 to 1279. These are the stories in the classic lamplight records and koan collections that are Zen’s shared history. As I explained in Circle of the Way, however, many of these stories aren’t so much history as myth. You might call some of them “fan fiction.”

One of the things I tried to do in the book was chart a course between the traditional stories and current academic scholarship into Zen history. Most of the time, the two things don’t line up very well. Frankly, most of the story of early Zen that we’ve all heard from teachers is post hoc invention to create a respectable backstory. This includes everything we’ve ever heard about Bodhidharma. It also includes the first thousand years or so of the transmission lineage, which appears to have been invented about the year 690 to enhance the status of a just-deceased teacher named Faru, or to enhance the status of the Shaolin Temple, where the lineage was first inscribed, or both.

Knowing this, what do we do with the tradition of lineage? Keep it. The charts are probably accurate for the past several centuries, which is worthy of respect. The tradition of transmission is well established and is the principle container that has enabled Zen to be passed from generation to generation for a very long time. I see no reason to change that.

There is no story more central to Zen’s identity than that of the 6th Patriarch, Huineng. For that we can thank the Platform Sutra, which is a wonderful text written in Huineng’s voice that expresses much wisdom. However, the academic scholars insist that the original Platform Sutra ― it got longer through the centuries ― was written about 70 years after Huineng died, and probably not by someone who knew him.

Some of the stories in the Platform Sutra about Huineng’s life couldn’t have happened, the scholars say. For example, the famous poetry contest that secured Huineng as the Sixth Patriarch couldn’t have happened, because Huineng and senior student Shenxiu did not study in the Fifth Patriarch’s temple at the same time.

But the Platform in many ways became the glue that held the Zen tradition together through the upheavals of the late Tang Dynasty and after, which some other Chinese Buddhist schools did not survive. The Platform’s teachings, whoever composed them, were embraced. The literary figure of Huineng, which may or may not bear much resemblance to the real Huineng, became the ideal prototype of a Zen teacher for a very long time. It elevated the Diamond Sutra, and the prajnaparamita sutras generally, as the scriptures most central to Zen, which they are to this day.

So, while the Platform Sutra should not be read as history, the Platform itself played a critical role in Zen history. What should we do with it now? Read it, study it, absorb it, as many generations of Zen students have done.

The koan literature is rich and useful, but it isn’t history. Some of these bits of dialogue and anecdote may be based on events that really happened, and some may be outright inventions. If you want to put them into the category of myth, that’s okay with me.

But to call something myth is not to say it isn’t true, just that it isn’t factual. Truth and factuality are not always the same thing. We’ve already seen that it’s possible to string selective facts together to express something false. By the same token, myths can express something that is deeply true but not easy to talk about.

I like something the religion scholar Karen Armstrong said about myth in an NPR interview some years ago. “Myth is about the unknown,” she said. “It is about that for which initially we have no words. Myth therefore looks into the heart of a great silence.” She also said that a myth is something that in some sense may have happened once but which also happens all the time.

So, for example, when we hear the story of the Second Patriarch who stood outside Bodhidharma’s cave in the snow and finally cut off his own arm to get Bodhidharma’s attention ― and then proceeded to have a sensible conversation ― we might suspect that didn’t really happen. But if you think that story is about two guys who lived in the 6th century, you’re missing the point. In truth, the story is about you. It’s about everyone who first walks into a Zen center or temple, full of questions and confusion, seeking the dharma. You may not have even known it was the dharma you were seeking, just that you thought were missing something. Or maybe your “standing outside in the snow” moment came, or will come, later in your practice. We may not literally have to stand in the snow outside a cave and cut off our own arm. But metaphorically, maybe. In some way. It’s up to you to work out how the myth relates to you. It’s up to you to clarify what you’re doing in Zen, and whether the thing you think you are seeking is really what you’re seeking, or if you were ever really missing anything. And then Bodhidharma will say, “I have put your mind at rest.”

So, we can appreciate myths as myths and history as history, as long as we don’t mix them up. When we do mix them up, it can have unfortunate consequences. For example, one of the points I make in the book is that the fabled connection between Zen and samurai warrior martial arts is way overblown. There’s a little bit of connection, but on the whole that connection is more myth than history. But it’s a myth that has been robustly romanticized and widely believed, and this possibly was a factor in the support of Zen institutions of Japan’s military aggressions in the 20th century. I believe that for a time this myth also impacted how western Zen identified itself. My first few sesshins back in the nineteen eighties struck me as being more like Marine boot camp than anything else. The atmosphere was very macho, very martial. I understand that a macho atmosphere permeated many western Zen centers and temples of the time. From what I’ve seen this appears be less true now, possibly because samurai macho Zen has smacked into western feminism. Which is just as well.

So let’s talk about the history as history. Something that I realized while I was writing Circle of the Way is that Zen doesn’t really have a starting point. In the traditional stories Zen is said to have been founded in China by Bodhidharma at about the beginning of the 6th century, give or take. But in truth all of the elements of teaching and practice associated with early Zen got to China before Bodhidharma did. And Zen didn’t become a distinctive school of Chinese Buddhism until some time after Bodhidharma was long gone. It appears the school wasn’t known collectively as Chan Buddhism until about the 10th century or so.

The Zen that China gave the world was, for the most part, Song Dynasty Zen. The Song Dynasty began more than four centuries after we believe Bodhidharma got to China. One of the academic historians I used as a source argues that Zen didn’t really become Zen until the Song Dynasty. This scholar, Morten Schlutter, even wrote a book focusing on Song Dynasty Zen history called How Zen Became Zen. It’s actually not too bad; I learned a lot from it.

But some might ask, if Zen wasn’t Zen until then, what was it before that? When did Zen begin? This reminds me a bit of the story of King Melinda’s chariot ― if you take it apart, at what point does the collection of parts stop being a chariot? And, of course, from the perspective of Buddhism, that’s the wrong question, since chariot is just an expedient designation for something that exists only in a relative sense.

Like all other phenomena, Zen is something composed of many parts, without self-essence, that came about because of ever-changing causes and conditions, and we identify it with a particular name because we have to call it something to talk about it. I argue that to fully appreciate what Zen is, one should know something about how it came together to be what it is now, which is what Circle of the Way is about.

I came to realize that the way the story of early Zen traditionally is told, with its focus on the Six Patriarchs, is not terribly functional. The whole emphasis on a patriarchal lineage obscures the presence and contributions of women, of course. But beyond that, I’m not sure the Patriarchs are all that important. You really see Zen taking shape in the early Tang Dynasty, which began in 618, through the work of teachers who were not Patriarchs. I’m thinking in particular of Mazu Daoyi, who gave us “ordinary mind is the way,” and Shitou Xiqian, who gave us the Sandokai ― the identity of relative and absolute. We could also thank the true author of the original Platform Sutra, another Tang Dynasty work, even if we don’t know who that was. I don’t have a problem calling these early masters “Zen” masters, even if they didn’t call themselves that.

Even before that, many of the contributions of the very early Oxhead school, which was founded roughly a century before Mazu started teaching, are still deeply embedded in Zen today. This deserves to be remembered. On the other hand, the Third Patriarch was probably a name picked out of a hat to serve as a patch between Number Two and Number Four.

After the Tang Dynasty and a messy interim period came the Song Dynasty. During the Song Dynasty the many loosely aligned lineages that claimed Huineng as a common ancestor became recognized as a distinctive tradition called Chan. Frankly, what pulled it together was not just teaching and practice developed by the Tang masters but also a boatload of shared myth that had been adopted as history and gave the widely dispersed teachers and students a shared identity.

During the Song Dynasty the bits of stories called koans were preserved in the classic collections, beginning with the Blue Cliff Record in 1125. Koan contemplation was invented in the 12th century and widely embraced, although the Caodong lineages maintained a meditation practice based on earlier forms. Dogen studied with a Caodong teacher in Song China and brought that tradition to Japan in the 13th century, calling it Soto Zen. Soon other monastics brought the koan-contemplating practice to Japan also and founded the Rinzai school.

Although Zen got to Korea earlier, there was enough cross-pollination between Korean and Chinese Zen during the Song Dynasty that it can be said the Zen of Korea evolved from Song Dynasty Zen. Zen got to Vietnam earlier, too, but Vietnamese Zen today mostly evolved from the teachings of Chinese Linji masters fleeing the fall of the Ming Dynasty in the 17th century.

This history is the basic foundation of Zen as it exists today, including Zen in the West. But Zen in the West is, I think, in a precarious place. It seems to be evolving in twenty directions at once. Sokei-an Sasaki said that bringing Zen to the West was like “holding a lotus to a rock, waiting for it to take root.” He believed establishing Zen in the west would take a few centuries, and he has yet to be proved wrong.

Since the Beat Zen era of the 1950s Zen has been in danger of being completely swamped by western popular culture, which may have embraced Zen as being cool but also wants it to be something other than what it is or has ever been.

In some ways it’s gotten worse since the Web was invented. All manner of people who clearly have little personal experience with a teacher and don’t know what end of the incense stick to light set themselves up as experts and spew their own opinions about Zen to the world, and it’s hard for traditional Zen to compete with play-pretend Zen. The Zen teacher James Ford wrote recently that such people “tend to contribute to a ‘dumbing down’ of our Western understanding of what Zen is. Bottom line there’s a lot of noise and a lot less signal, as some might say, out on the inter webs.”

At the same time, people who are sincerely practicing in the Zen tradition face many challenges about how to make it work. In Asia, although there have been lay Zen students since at least the early Tang Dynasty, it has always been primarily a monastic tradition. Yet most of us in the West are lay students, with jobs and families and overstuffed schedules. The old Asian model, in which monastics do most of the practicing while laypeople support them with alms, just doesn’t work here. As I wrote in Circle of the Way, there’s a lot of experimenting going on right now to figure out how to make teaching and practice more accessible to laypeople. And I wish us all a lot of luck.

But at this very fluid and precarious moment in Zen history I strongly suggest that Zen take ownership of its history, by which I mean history and not just the traditional stories. I spent the large part of three years immersed in contemporary scholarship on Zen history, and let me say that the academics, with very few exceptions, are making a mess of it. They get the facts and dates right, I assume, but their conclusions and interpretations, especially of the teachings, are often ridiculous. I have compared them to tone deaf people who write histories of opera. And some of them obviously hate opera and don’t know why anyone listens to it.

My editor at Shambhala told me that he had once hoped to pursue an advanced degree in Buddhist studies. He gave up on the idea because one of the professors for his undergrad honors thesis, which concerned the modern history of Zen, was openly antagonistic to Zen. Perhaps that was just one teacher, but I have seen the same antagonism in much of the current scholarship.

There’s a wonderfully snarky critique of academic scholarship on Zen that was written by Victor Sogen Hori, whom you might recognize as a Zen scholar who has published some wonderful work on koans. Sogen, a Canadian, spent 13 years studying as a monk in Japan and also has a Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University, so he’s someone with a foot in both worlds. Anyway, he wrote an introduction to Volume 2 of Heinrich Dumoulin’s Zen Buddhism: A History, in an edition published in 2006 by World Wisdom. It’s worth looking up and reading. He calls out prominent, still influential scholars who portray Zen as a bad joke and nothing but a vast game of deception. And I cite some of these same scholars in my book, because they are the mainstream of academic study. But I concur with Sogen’s opinion.

It would be great if we could open a respectful dialogue between Zen practitioners and the academic scholars, but frankly at the moment I don’t think that’s possible. I’ve seen some attempts already that did not go well. The current crop of academics too often assume that they must discount our opinions of our own tradition because, obviously, we cannot be objective, but they are blind to their own biases. But for that reason, the academic scholars must not be entrusted as the sole guardians of Zen history.

And this is important to us, because we need a respectful but honest accounting of the history to keep us grounded as we go forward. The history is embedded in Zen teachings, whether we know it or not. It is reflected in the liturgy, robes, and rituals, and in zazen itself. Some of the old myths may or may not transfer well from Asian to western culture and might be tweaked or eliminated. But the history is what it is. And it’s a wonderful history. For the most part. And the parts that are less than wonderful need to be acknowledged and understood, too. We can learn from them.

My teacher Jion Susan Postal used to talk about what she called the “three infinities.” I believe this formula was original with Susan. These are infinite kindness to the past, infinite service to the present, infinite responsibility to the future. These three infinities cannot be separated. By taking good care of the present, we take care of the past and future as well.

By understanding and appreciating Zen history ― our history ― we can better understand ourselves as Zen students and teachers. And by better understanding our history we can do a better job of taking care of this incredible legacy we’ve been given by our dharma ancestors.