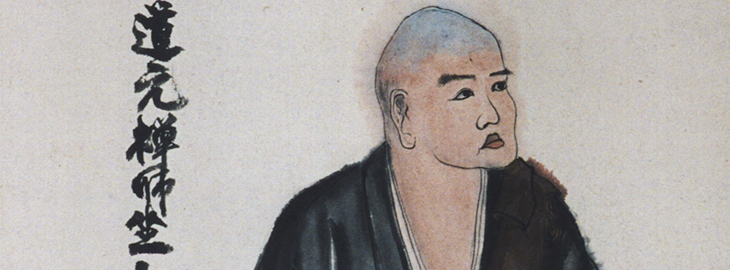

Eihei Dogen (1200-1253), the founder of Japanese Soto Zen, left us a large body of written work celebrated for its beauty, depth and subtlety.

However, the way Dogen’s writing is organized can be confusing. Often most of Dogen’s written work is lumped together under the title Shobogenzo, or “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye.” However, Shobogenzo is not one single, definitive collection of Dogen’s work. There are several Shobozengos containing different numbers of texts, and there are important texts not included any of the Shobogenzos.

This article provides a brief overview of how Dogen’s writing has been collected.

Kana Shobogenzo

The Kana Shogogenzo is made up of shorter works referred to as fascicles, a term borrowed from horticulture. An example of a fascicle in the plant world would be a cluster of needles on a pine tree. In literature, a fascicle is a discrete section of a book that could be pulled out and published separately.

Most of the Shobogenzo fascicles originally were sermons that were recorded on scrolls by a student and edited by Koun Ejo, Dogen’s successor. After Dogen’s death, as Soto Zen spread through Japan, many scrolls were carried to new temples, then stored away and forgotten. When rediscovered centuries later, scholars were put to work trying to fit the pieces back into the whole.

The various Shobogenzos are distinguished by the number of fascicles they contain. When people talk about “the” Shobogenzo, usually they are referring to the 95-fascicle Shobogenzo. But there are other Shobogenzos containing 12, 28, 60, 75, and 80 fascicles.

75-Fascicle Shobogenzo. This Shobogenzo was compiled by Dogen’s disciple Senne, a work that was completed in 1263. The first fascicle is “Genjokoan,” one of Dogen’s most beloved texts. Other fascicles in this collection familiar to most Soto Zen students include “Uji” and “Zazenshin.”

95-Fascicle Shobogenzo. During the late Edo period of Japanese history, all Buddhist sects were required by the Tokugawa shogunate to define themselves and explain their basic teachings. To fulfill this requirement, the monk Kozen compiled all of Dogen’s work available to him into the 95-Fascicle Shobogenzo, published in 1690. Among the texts added to this Shogogenzo that were not in the 75-fascicle version is “Bendowa,” an important early work of Dogen’s that had been lost and re-discovered in the 17th century.

The 95-Fascicle Shobogenzo is considered authoritative by many scholars. However, other scholars point out that the fascicles from the earlier Shobogenzo were in a very different order, and the earlier version more likely reflects the order Dogen preferred.

12-Fascicle Shobogenzo. The 12 fascicles in this Shobogenzo are from the later years of Dogen’s life. The fascicles were compiled by Dogen’s successor Ejo, and the collection possibly was published in 1255. But for centuries only part of this Shobogenzo was known to exist. At long last a complete copy of the 12-Fascicle Shobogenzo was discovered at Yokoji temple, Ishikawa prefecture, in 1927.

Other Kana Shobogenzos. Through the centuries other attempts to reconstruct Shogobenzo have been made by monks and scholars. The best known of these are the 28- , 60- , and 84-Fascicle Shobogenzos, although there are others. Today these are mostly of interest only to historians.

Other Shobogenzos

Mana Shobogenzo. This is also called the Sambyaku-soku Shobogenzo or the 300-Koan Shobogenzo. It is a collection of koans, in Chinese and without commentary, compiled in three volumes of 100 koans each.

This text was lost for many centuries. The middle volume was discovered in 1934, and the remainder came to light in the 1980s, The discovery of the Mana Shobogenzo is significant primarily because it sheds new light on Dogen’s approach to koans.

Shobogenzo zuimonki. Sometimes called “Recorded Sayings” or “A Primer of Soto Zen,” the Shobogenzo zuimonki contains comments on institutional structure and instruction and several informal sermons. It was written by Dogen in the mid-1230s.

Not Shobogenzo

Not all of Dogen’s work is found in a collection with “Shogobenzo” in the title. Of the several other collections of Dogen’s poems, essays and sermons that have been compiled and published over the years, two are deserving of special mention.

The Eihei koroku, or “Extensive Record,” was written in Dogen’s later years as abbot of Eiheiji. It includes formal instruction to his monks, informal talks, and commentaries on koans. Many teachers and scholars consider the Eihei koroku to be as important as the Shobogenzo.

The well-known early work “Fukanzazengi” was written independently and later included in the Eihei koroku. However, parts of “Fukanzazengi” are repeated in fascicles collected in the 75- and 95-fascicle Shobogenzo, “Zazengi” and “Zazenshin.”

Another collection associated with Eiheiji is the Eihei shingi. The Eihei shingi is made up of essays collected in 1502 and published for the first time in 1667. Its most well-known essay is “Tenzokyokun,” or “Instructions for the Cook.”

Reading Dogen

Bound editions of the complete 95-Fascicle Shobogenzo are very expensive, but English translations can be downloaded free from the Web. The translation by Gudo Wafu Nishijima and Chodo Cross is highly regarded for its accuracy. The Shasta Abbey translation is more readable but not always accurate. For a lovely, readable sampler of Dogen’s work, I recommend Moon in a Dewdrop, edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi.

[This is an article I wrote for the Buddhism section of About.com. However, since About.com has removed it from their servers, all rights revert to me.]